The cancer revolution is here

“It’s cancer,” is the diagnosis everyone dreads to hear. Yet in 2018, more than 46,000 people in NSW are likely to have received this devastating news.

While the feelings of despair around a cancer diagnosis are inevitable, the prognosis for recovery in cancer patients is changing at a revolutionary pace.

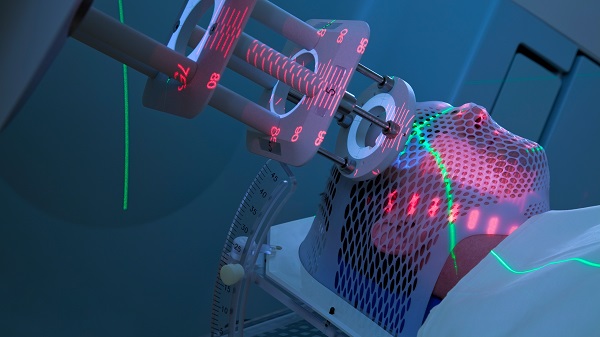

Advances in the speed and precision of diagnosis; refinement of surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy; and the development of new immunotherapies for formerly untreatable cancers mean that outcomes for patients have dramatically improved in recent decades.

Across the state, the five-year survival rate is almost 70%, says Professor David Currow, Chief Cancer Officer and CEO of the Cancer Institute NSW. As recently as the 1980s, it was just 48%.

For some patients, such as those with advanced melanoma, the change in outcomes over the past five years has been nothing short of spectacular, he says. “It’s really fantastic to see people with advanced disease have it just melt away with the new drugs that are available.”

The cancer revolution might appear to be all about new treatments and technologies, but like all revolutions, it’s as much about the people who are delivering and developing them.

It’s about fostering more effective collaborations between researchers and clinicians, and inclusive new approaches to clinical care.

Early and personal

Early detection followed by rapid and accurate diagnosis is still the most effective way to cure cancer. Most cancers are successfully treated because they were found soon enough, surgically removed, and perhaps followed up with chemotherapy or radiotherapy, explains Currow.

Advances in the speed and cost of genome sequencing have allowed widespread testing for specific gene mutations that increase the risk of developing certain cancers, such as the link between the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes and breast and ovarian cancers.

Rapid and affordable genome testing has also allowed for accurate diagnoses to be returned in the space of days, rather than weeks. Rapid diagnosis allows patients to make more informed decisions about the care choices they face, says Currow.

Advances in genome sequencing are also leading to more personalised cancer treatments.

The Garvan Institute’s Genomic Cancer Medicine Program is investigating how particular genetic changes within the cancer itself can be used to predict which therapies will be the most effective in an individual patient, or how more targeted treatments can be applied.

Because cancer cells are our body’s own mutated cells, their genetic make-up varies from person to person. This means each cancer has its own genetic ‘fingerprint’.

As the cancer progresses, the cells continue to mutate, so their genetic make-up also continues to change. This could explain why some cancers become unresponsive to treatment over time.

Proteomics – the analysis of proteins expressed in cells – is emerging as a promising method of understanding another aspect of that cancer cell ‘fingerprint’.

“I think we’re at the start of a very steep learning curve to understand how the protein fingerprint of the cancer itself can help direct therapies,” says Currow.

Rigorous comparison, genuine collaboration

Clinical trials, which rigorously compare new and emerging therapies with existing therapies, have been key to advances in cancer treatment, says Currow.

Phase III clinical trials evaluate whether a new treatment is superior to an existing standard treatment. Emerging evidence suggests that there may be an ’inclusion benefit’, whereby all patients involved in a clinical trial have better outcomes, regardless of which treatment they receive.

Patients involved in clinical trials all receive at least the current standard of care, and potentially also benefit from closely adhering to a treatment regimen, receiving increased care and follow-up, and changing their own health behaviours as a result of being involved.

The benefit of clinical trials may also extend to cancer patients who are not taking part in a trial. Some research suggests that patients who are treated in hospitals that regularly participate in research have improved outcomes, and that a strong research culture also benefits hospital staff.

“Clinical trials, for us, are not just about evaluating new interventions. It’s also about improving the quality of care that’s offered across the system,” says Currow.

The Cancer Institute NSW funds seven translational cancer research centres to facilitate the rapid translation of research findings into improved patient care.

As Currow explains, realising the full potential of new and emerging cancer therapies requires collaboration between researchers and clinicians across institutional and administrative boundaries.

“We want to see the best people working together, no matter where they come from in the health system or academia,” he says.

The era of precision medicine also requires clinicians to work together more effectively, as no individual clinician can have specialist skills in all aspects of cancer treatment.

This means the emergence of a genuine community of practice over the past decade has already translated into better outcomes for patients, says Currow. For him, this is the future of personalised cancer treatment.

“How do we take all of this knowledge and systematically apply it to the individual, for the individual’s benefit?” he asks.

“If we get that right, we’re going to see a rapid diminution in side effects and harms, and a rapid increase in outcomes.”

By Viki Cramer

Updated 4 months ago