Microbiome and the mind: How the gut influences mental health

If you’ve ever felt sick with worry, gone with a gut instinct or felt butterflies in your stomach, you know the link between brain and bowel is strong.

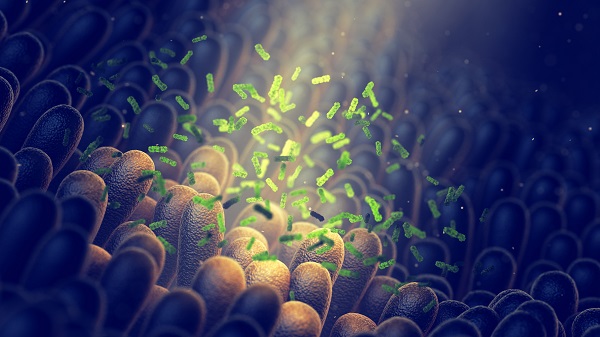

And in recent years, evidence has emerged to show how the extraordinarily vast array of microbes parked inside your intestine – the gut microbiome – feeds into mental illness development and progression.

“Depression, anxiety – these and other disorders are directly linked to what happens in the gut,” says UNSW Professor of Medicine and consultant gastroenterologist Emad El-Omar.

So how do colonies of bacteria, viruses and other bugs in your intestinal tract influence what goes on in your skull?

Our gut microbiome helps us digest food and regulate our immune system, generating metabolites as it goes. As our microbial populations shift, so too do the metabolic compounds pumped into our gut.

Should these metabolites make their way out of the gut and into the intestinal wall, they can directly interact with our enteric nervous system or ‘second brain’. These 100-million-odd nerves embedded in gut tissue transmit messages to the brain in our head.

Metabolites may also communicate with the plethora of immune cells that surround our digestive system, triggering an immune response, or slip into the bloodstream to be ferried around the body.

Such interactions have the potential to trigger and sustain chronic brain inflammation, which is linked to depression and anxiety. Indeed, some people with depression or anxiety benefit as much from anti-inflammatory drugs as they do antidepressants.

Can microbiome manipulation mend minds?

In the past decade, the microbiome has surfaced as a target for psychiatric treatment.

While there is a strong genetic component in almost all mental illnesses, “there’s not much you can do to change your genes, whereas the microbiome is eminently manipulatable”, adds El-Omar, who is also director of UNSW’s Microbiome Research Centre (MRC).

A healthy diet, exercise, some medications and faecal microbiota transplants can all shore up the gut microbiome, as can next-generation pre- and probiotics. These targeted supplements nurture conditions for, and repopulate the gut with, specific beneficial bacteria.

Microbiome fine-tuning may also help offset serious medication side effects. For instance, long-term use of some common antipsychotic drugs increases a patient’s risk of cardiovascular disease.

This may be driven, at least in part, because many antipsychotics are lethal to ‘good’ gut microbes, at least when cultured in the laboratory, El-Omar says.

“So you have to think: are antipsychotics knocking off some of the beneficial microbiota that protect people from things like cardiovascular disease and obesity?”

To find out, MRC researchers and collaborators at the Prince of Wales Hospital and Neuroscience Research Australia (NeuRA) last year started recruiting for a longitudinal study to investigate microbiome changes in patients with schizophrenia.

Of interest is a bacterium, found in the gut of lean, fit folk, called ‘Akkermansia muciniphila’.

“A. muciniphila is regarded as a potential next-generation probiotic and, in fact, you don’t even need to eat the live bacteria,” El-Omar says. “You can heat-inactivate the bacterium or extract an outer membrane protein and administer that for the same impact.”

When administered as a supplement, it provides metabolic benefits in pre-diabetic overweight and obese people. “It would be fascinating to try this for schizophrenia patients,” El-Omar says.

The hope is the probiotic may mitigate some of the microbiome-disrupting effects of antipsychotics, but “we need to do the clinical studies”, he adds. And that’s not just to show A. muciniphila’s efficacy – it’s for all microbiome therapies.

“Before we can make any claims, we must present the clinical evidence base – this is the reason the MRC exists; to investigate those stories,” El-Omar says.

“Microbiome research is a new kind of revolution. We’re very excited about it, because it really is an opportunity to bring huge benefits to our patients.”

Updated 4 years ago