Five ways health research translates into real-life solutions

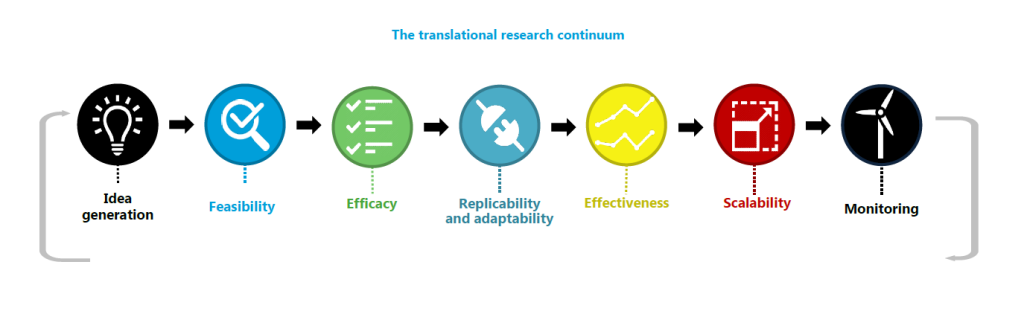

The Translational Research Grants Scheme aims to incentivise research that is a priority for the State, or articulated in local strategic research plans, to support the translation of research into policy and practice.

Image credit: Sax Institute

Here are five projects funded by NSW Health’s innovative Translational Research Grants Scheme (TRGS) that used the latest evidence-based research to find solutions for key health problems.

1. Improving care for Borderline Personality Disorder

Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) can have devastating effects on a person’s life, not to mention their family, and around 10% of patients with BPD will die from suicide.

The main tool in improving care for BPD is alleviating pressures on inpatient and emergency services, which can lead to lengthy waiting times for treatment, particularly for those at highest risk of self-harm.

That is why NSW Health funded researchers to discover whether a new approach to care can deliver better results, slash waiting times for treatment for those most at risk as well as reducing funding pressure on the health system.

The new “stepped care” approach involves a series of interventions from the least to the most intensive, matched to the individual’s needs. Those responses include the Dialectical Behaviour Therapy group program, which is shorter in duration and cheaper to deliver than individual therapy. This model of treatment is central to the Australian Government’s mental health reform agenda.

Researchers are testing how well this system works, comparing outcomes between treatment as an individual or within a group, how long any positive changes last for after treatment, and how the treatment would fit into current services in NSW.

They hope the stepped approach will result in a reduction in BPD and associated mental health symptoms, as well as a more efficient use of health services, and fewer emergency department visits and inpatient admissions.

2. CIRCUITS – helping people with schizophrenia

Schizophrenia can be crippling for patients whose cognitive problems make it a struggle to perform everyday activities. This forces many into assisted living or, at the very least, means they need a high level of personal support.

One program that has shown promise overseas aims to improve patients’ insight into their functional difficulties in key areas of cognitive functioning and suggest strategies to help overcome them.

NSW Health, through its TRGS, backed research to investigate the computerised cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) program called CIRCUITS. The study aimed to discover, first, what patients and staff in mental health services think about the program and second, whether the intervention can improve everyday functioning and relationship building.

CIRCUITS is an animated internet-based program, which engages patients in graded real-world tasks within a virtual village. These include using public transport, meal planning and shopping as well as interactions with members of the community.

The initial TRGS study is expected to lead to further research, perhaps including clinical trials, working towards an evidence-based translation of the program across NSW Health services.

3. Coping with complications of diabetes

One of the debilitating complications of diabetes is the development of foot ulcers due to problems with their blood circulation. This is painful and can have a devastating effect on quality of life. If not managed properly these foot ulcers can, in extreme cases, lead to amputation.

We’ve known for a long time that the removal of dead tissue can promote wound healing, but, until now, there has been no evidence-based information on how frequently this treatment should take place.

Under a Translational Research Grant, researchers are testing out weekly and fortnightly treatments for a random selection of patients to see if more frequent treatment improves ulcer healing for people with diabetes.

By knowing what schedule works best for the majority of patients, NSW Health will be able to deliver the best outcomes for patients while maximising the efficiency of podiatry services.

4. Recovering after a stroke

Surviving a stroke is often only the beginning of recovery, with patients left unable to function as they did before, and facing a long journey of rehabilitation.

Occupational therapists have a set of evidence-based guidelines on the best way to approach this rehabilitation, with the best chance of improving the patient’s functioning following stroke.

But the problem is that often occupational therapists only have limited direct contact during rehabilitation when they can make sure that the guidelines are implemented, and this contact can be even more difficult in regional or rural areas. If patients could manage more of their own rehabilitation at home, adhering to the guidelines, researchers believe that it could speed up rehabilitation and improve outcomes in regional areas.

Research suggests this self-managed process, supported by weekly telephone coaching with an occupational therapist for six weeks, and access to the rehabilitation resources for 12 weeks, could deliver better results more efficiently.

5. Improving Aboriginal follow-up care

Aboriginal patients in NSW are more likely to report inadequate follow-up health services than non-Aboriginal patients. Aboriginal patients are also 2.5 times more likely than non-Aboriginal patients to take themselves out of hospital against medical advice. That can mean higher rates of unplanned readmissions or visits to emergency departments compared with non-Aboriginal patients.

Researchers addressed this problem by developing the Aboriginal Transfer of Care (ATOC) model which, a pilot study showed, led to decreased readmissions from 15.6% to 5.7%.

The ATOC model starts with a multidisciplinary team planning follow-up care within 24 hours of a patient’s admission. They will make sure the patient and their family understand the plan, brief the patient’s GP or Aboriginal Medical Service and community providers, and ensure that the patient has the necessary medications, equipment and written information the day before they leave hospital.

TRGS-funded research is now testing whether the pilot study findings can be replicated in a large study, as well as looking at the response of Aboriginal patients and staff to the model.

Updated 6 years ago