A more comfortable user-friendly device to monitor labour and avoid complications

Being in a hospital about to give birth is uncomfortable enough. So why is a medical instrument meant to protect mother and baby seemingly designed to add to this suffering?

Dr Sarah McDonald contemplated this after complications during her son’s birth. She was hooked up to a cardiotocography (CTG) machine, which monitors fetal heart rate and uterine contractions. Transducers strapped or stuck onto a pregnant woman’s belly relay information to a printer-sized unit, where clinicians analyse readouts.

But for CTG to provide valid readings for interpretation, women are often asked to remain still – which can be uncomfortable and difficult for a labouring woman.

“We require women to work around the technology, but we should be designing technologies that work around the user,” McDonald says. And when she explored further, she discovered fundamental CTG technology had remained pretty much unchanged since its invention midway through last century.

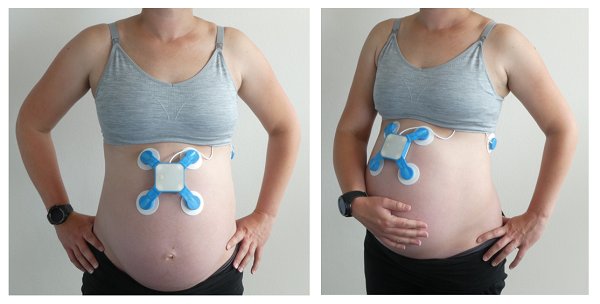

In response, McDonald started a PhD in biomedical engineering while developing a new, more user-centric CTG technology. Dubbed Oli, the compact device sticks to a pregnant woman’s belly and picks up signals from mother and baby. Unlike a traditional CTG, Oli’s not tethered to a hefty external unit, so the mum-to-be has the freedom to sit up, lie down or pace around – whatever’s most comfortable for her.

To help get the device onto the market, in 2017 McDonald completed the Medical Device Commercialisation Training Program, which consists of intensive courses and a workshop series to help inventors take their medical devices to market.

For the “customer discovery” section of the program, she conducted hundreds of interviews with parents, midwives and obstetricians and uncovered a sobering fact: while everyone recognised that current CTG technology had significant drawbacks, no-one was doing anything to address them.

“Something important I took from the course was that we need to be encouraging people not to see a problem and complain about it, but actually take it upon themselves to help rectify it,” McDonald says.

Also in 2017, McDonald and her company, Baymatob, won their first Medical Devices Fund grant. The money supported the development of a more advanced iteration of Oli, where the sensor component relayed information to a smartwatch. They then tested it on animals – but not the ones you might expect.

“It certainly was interesting attaching the device to horses and camels!” McDonald laughs. But the challenges were well worth it – that quadruped data shored up existing preliminary data from some 80 women.

Next, Baymatob broadened its clinical input base beyond the Royal Prince Alfred hospital in Sydney to others in NSW and, more recently, the United States. Feedback from these sites, along with input from global health organisations, soon made it apparent that the smartwatch component needed to go.

There were a few reasons for this. How off-the-shelf third-party services collect and store sensitive medical data can present privacy risks, and must be assessed and managed carefully within hospital and regulatory requirements.

Another came down to comfort. “Cellular-enabled smartwatches are designed for a male’s wrist – they aren’t the daintiest of all things – so comfort was a big factor, especially for someone who is close to or in labour,” McDonald says.

So using funds from a second Medical Devices Fund grant in 2019, Baymatob are working to enhance Oli by ditching the watch, and improving the CTG device’s battery life and capacity to collect higher quality data, and more of it.

One proposed function of the new and improved Oli is a capacity to predict fetal distress, allowing clinicians to act before the situation escalates. Currently, if something looks slightly amiss on the CTG output, clinicians will “watch and wait” – that is, monitor with regular checks.

“But what they can’t do is look at the precursors to things that lead to fetal distress, and that’s something our product hopes to offer,” McDonald says.

“We call it predictive monitoring. Before something goes wrong, you should be able to pick up warning signs, so it is hoped you can do smaller interventions and get back on course before it gets to a catastrophic point.”

Just last year, McDonald attended a pre-submission meeting with the US Food and Drug Administration, and another with Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration. “Without the course, there’s no way I would be anywhere near equipped to do those,” she says.

In 2020, McDonald plans to run a multi-site pilot study to further optimise the device and prepare for clinical trials.

Getting Oli to the point it is today could not have been possible without her crew, McDonald adds. “We have a fabulous team from all walks of life – several mothers as well as younger ladies and gentlemen pre the family stage – not to mention all the fantastic midwives, obstetricians, hospitals and other clinical experts assisting and advising us. This mix is crucial to our development.

“We have achieved a lot in the past few years, but that’s not just Sarah – that’s Baymatob.”

By Bel Smith

Updated 4 years ago